Conditions for Change

An understanding of current conditions—as well as past and future trends—is helpful in identifying critical constituencies and the issues that might animate them. It is also useful to look at not only where the state is (or has been) but also the direction in which the state is headed. For this, we turn to the Conditions for Change: Demography, Economy, Politics and Geography.

This site offers two ways to explore the Conditions for Change: per-state tabular data and interactive story maps. For state-level data, simply select your state of interest from the one of the forms on this page. For interactive maps, choose your Condition for Change of interest from the choices below.

Interactive Maps

Demography - Choose a State

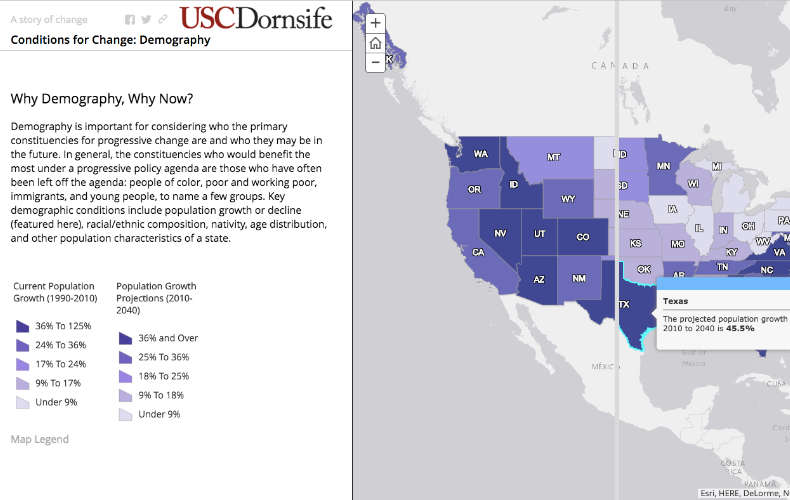

Are demographics destiny? It's hard to miss the focus on the question of population in U.S. politics. How can data and research on who lives in a state guide our work for a progressive future? We take you through some demographic conditions that have been proven to shape questions of racial and economic equity, and in turn, the pathways for progressive governance.

Population Growth - 1990-2010

Understanding the type and pace of population growth is key to understanding the demographic landscape of a state. Moreover, people of color, low-income communities, immigrants, and young people are among those who would benefit under a progressive policy agenda, so understanding growth (or decline) among these populations is also critically important.

Population Projections - 2010-2040

We recommend not only looking at past population growth, but also looking to the future, as population projections signal where a state is going in terms of diversity, and with it, future working and voting populations—critical in analyzing the possibility for progressive governance in your state.

Racial Generation Gap

The racial generation gap measures the difference between the percentage of youth of color (under age 18) and the percentage of seniors of color (age 65 or older). A larger gap means increasingly young populations of people of color in a state, meaning that the future is going to include much larger populations of voters and workers of color.

Percent Foreign Born

Understanding both the current snapshot, as well as the pace of growth, of foreign-born populations is critical to understanding economic trajectories as well as assessing pathways for progressive governance—as immigrants generally benefit under a progressive policy agenda.

Economy - Choose a State

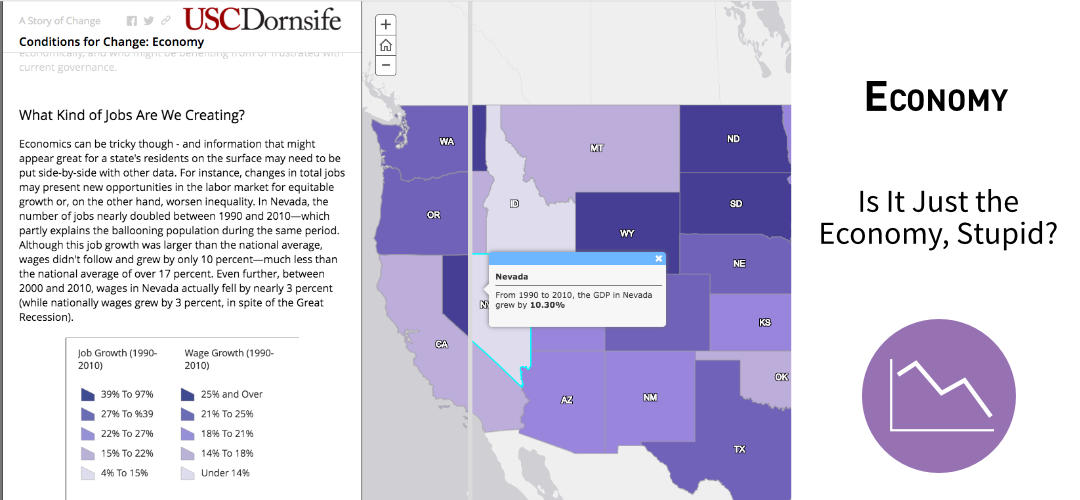

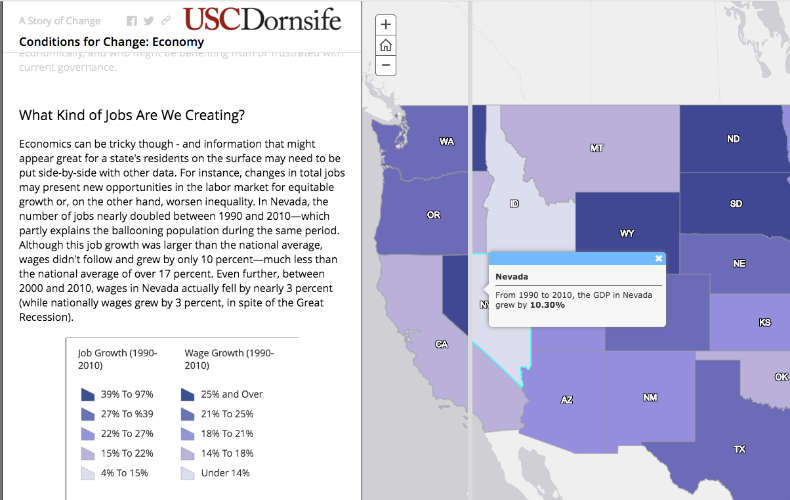

Is it just the economy, stupid? From jobs to poverty, wages to working conditions, economic questions often define how we even think of progressive change. Indeed, economic structures shape a state's labor force, policy priorities, and power relations. Here we show some sample metrics that can signal economic challenges and opportunities—and so potential pathways toward progressive governance.

Job and Wage Growth - 1990-2010

More jobs is always a good thing, right? Well, wages matter too. In order to achieve a just society, we need the growth of good jobs that pay people a living wage that keeps them out of poverty. Keeping an eye on both job and wage growth helps us get a sense of whether or not a state is growing in an equitable way.

Jobs to Population Ratio

A jobs-to-population ratio gives us a sense of the health of a state’s economy. A high ratio means jobs are keeping up with population growth, and a low ratio means jobs are lagging behind population growth. Unlike GDP, this measure helps us better understand the distribution of economic growth.

Working Poverty Rate

This metric shows the percent of those who are working full-time but are not making enough to sustain a family or a stable living. Many point out that the federal poverty level is too low to reflect current cost of living, so for "working poverty", we include full-time workers between the ages of 25 and 64 who fall below 150 percent of poverty.

Gini Coefficient

The "Gini" coefficient is one of the most commonly used measures of inequality and is fairly easy to interpret: the higher the gini, the more unequal the state. Not only is it an important economic metric, but a potential “hook” for organizing for progressive change.

Politics - Choose a State

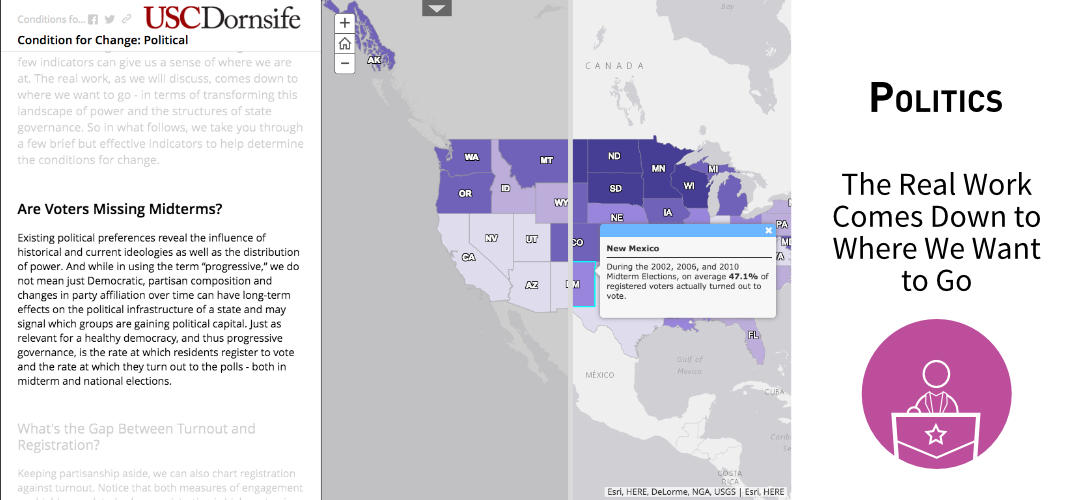

Partisan composition and changes in party affiliation over time can have long-term elects on the political infrastructure of a state and may signal which groups are gaining political capital. But just as relevant for progressive governance is the rate at which residents register to vote and the rate at which they turn out to the polls. So here, we present a few brief but effective indicators to help determine the political conditions for change.

Union Membership Rates 1990-2010

We include unions in our assessment of political conditions as they are the traditional entity that organizes and mobilizes workers. In recent decades, unionization rates have declined, which has dramatically re-shaped the progressive political calculus in states.

Voter Registration and Turnout in Midterm Elections

Overall, midterm elections have lower rates of voter turnout than presidential ones—but these elections are critical as they often determine the fates of statehouses and, in many states, courthouses.

Voter Registration and Turnout in Presidential Elections

We explore both voter registration and turnout to understand ease of voting at different stages of the process. Rates vary among states due to factors like level of voter restrictions that disenfranchise voters of color.

Voter Registration vs. Turnout on Average

Another way to understand voting patterns is to look at averages over time, including both midterm and presidential elections. These rates help us see where a state may be in terms of citizen engagement overall.